But who were sent to Ushuaia? Apart from the convicts that had to serve the severest sentences and from those who also had to serve a cumulative penalty of indefinite time confinement, those entire prisoners lodge in the National Penitentiary that shared certain characteristics were sent to that distant site that they used to call “La Tierra” (The Land). So, periodically, there were new lists of the ones chosen. Their criminological background, behavior, learning in workshops, visits, sort of offense and the commotion they had produced on society were previously studied.

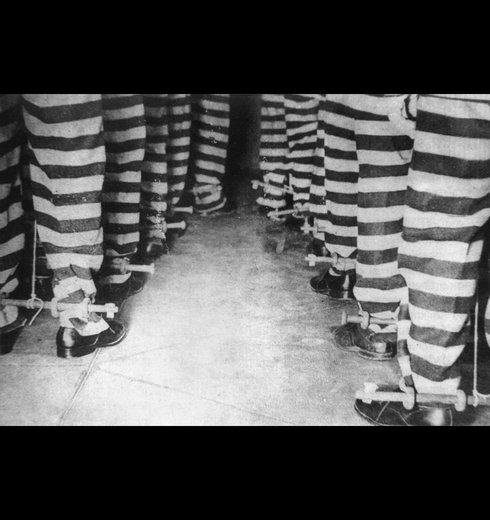

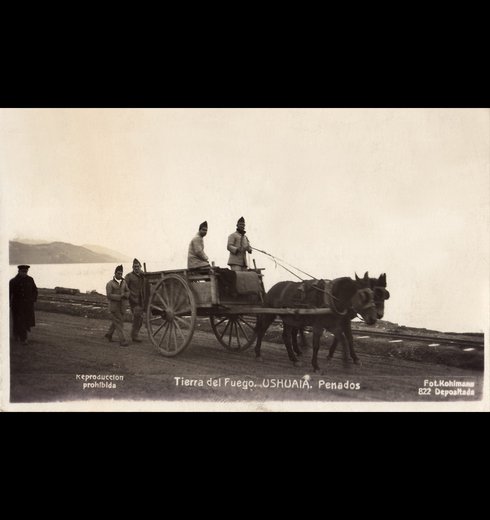

Convicts had to undergo a medical examination. When the departure day came, watchmen were in charge of informing prisoners about this after supper. The whole Penitentiary experimented a silence full of fear, anguish and suspense. Finally, transfers depended on the number of “chosen convicts” that could be lodge in the prison of Ushuaia. The next step was to get them to prepare a “bundle” with their cloths and utensils to be then led to the grating yard where they were examined in case they carried forbidden articles such as weapons or tools. Once they went through this revision, shackles were put - joined between them by an iron chain or bar - round their ankles so that they could not pace farther than 15 to 20 centimeters. Three hammer blows on every iron nails must have been three heavy blows on the heart of every convict waiting in formation and on those that were waiting in their cells for a change of destination. It is said that most hard and insensitive convicts looked at the blacksmith with arrogance while he was doing his work, but once they walked a few meters their spirit broke down as they began to feel how iron hurt their skin, how limited their movements were, and realized what their fate was.

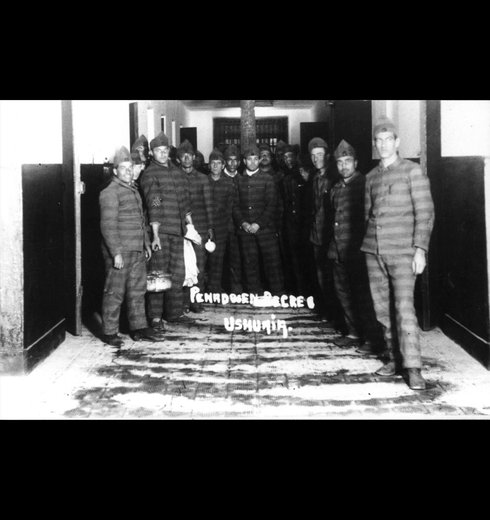

They were taken to the ship by trucks that belonged to the police. Then, prisoners boarded navy transports such as “Chaco”, “Ushuaia”, “Pampa”, “Patagonia”, “1º de Mayo” and they were placed in the hold with a large chamber pot. They remained there for about a month - the time that the voyage took. Fine dust from coal came into the holds, so prisoners arrived covered with it and letting the black dust out when coughing. According to some chronicles, on many occasions commanders of ships were merciful and allowed convicts to go out and take air and there were others that even made the shackles were removed. It is worth remembering that these voyages that joined Buenos Aires with the south part of the country not only took prisoners but also goods to Bahía Blanca, Puerto Madryn, Comodoro Rivadavia, Santa Cruz, Río Gallegos; and - of course - everything necessary for life in Ushuaia ranging from provisions and medicines to newspapers.

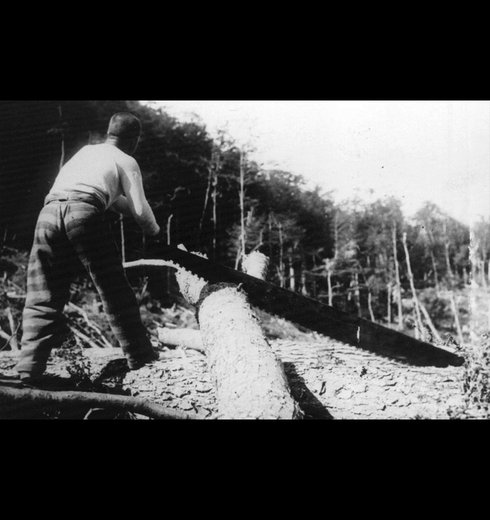

It is true that, at first, the selection of convicts was somewhat arbitrary. From 1884 - when Lieutenant Augusto Lasserre took the first convicts -, they were chosen for their manual skill to be useful for the building of the lighthouse of Isla de los Estados and of the sub-prefecture. As time went by, men and women prisoners were sent with the aim of settling down the penal colony. In the case of military prisoners, just a few were allowed to go with their wives.

Towards the end of the 19th century, minors were sent, even those who were just street children - as we call them nowadays. This changed during the first decade of 1900. It is believed that Carlos Gardel or Charles Gardés could have been to Ushuaia at that time. The last important change took place in 1936 when the Head Office of Penal Institutes took over the effective superintendence of the prison of Ushuaia. From then on, the treatment the prisoners received and their everyday life changed completely. The Classification Institute was set up and convicts were sent to the south according to their dangerousness and their difficulty for adapting to the penitentiary regimen. An article from the Penal and Penitentiary Magazine headlined “Sending of Convicts to Ushuaia” of 1939 reads: “Convicts age and health - both bodily and mental - were equally taken into consideration to avoid moving those that, although fulfilling legal conditions, could not be transferred because of the situation above mentioned. To decide which prisoners would make up this group a board of physicians was appointed. This board, assembled at the Penitentiary Institute, analyzed thoroughly each case on the lists. Those included in art. 51 of the Penal Code, having a short time of their sentences to serve, were also excluded as there was no point in moving them. Most of the components of the shipment are included within the resolutions of article 52 of the Penal Code.”